Members' experiments

Can Persian clover be used as a no-dig green manure?

Background

There are undoubtedly many advantages to no dig growing. These include reducing damage to soil structure and microbiological life, and potentially lower labour costs for cultivation and weeding. Such systems make good use of mulches and applications of compost to supply soil fertility and suppress weeds.

Green manures are often considered to be one of the most sustainable ways of supplying soil fertility as they fix nitrogen from the air. On plots where people dig their soil, green manures would be dug in so that they can release the nutrients for the next crop. To use them in a no-dig system, they are either cut down or left to die back then left as a mulch on the soil surface. They may need to be covered to help them break down more quickly.

We thought that Persian clover may be well suited for this task. This crop has only made an entry into the UK green manure scene comparatively recently. However, for a few decades, it has been a very popular crop in New Zealand. It is a rapidly growing annual producing a large amount of fleshy leafy matter. Later in the season, purple flowers are produced in abundance giving off a strong smell of sherbet. It then dies down, and the fleshy material rots down very quickly. We think that this would make it ideal in no dig systems as it has very little need to be dug into the soil.

This experiment compared Persian clover with crimson clover, a more tried and tested annual green manure.

Aim of this experiment

The aim of this experiments was to assess the potential of Persian clover as a mulching green manure for no dig systems. Members sowed Persian and Crimson clover alongside each other in early spring, compared their growth throughout the summer. They then left them to rot down as a mulch over winter and observed the soil conditions for the following crop in spring.

Growth of the crop

We recommended that people sowed the clover in mid-March. This is a standard time that many growers sow green manures to ensure that there is adequate moisture in the soil for germination. In 2016, the conditions in March were cooler than normal, and it would have been better to delay sowing until the soil had warmed up. Under these conditions, 27% of people’s crops failed to germinate. Additionally, 43% of people reported that the plants germinated but then ‘disappeared’ and the crop failed to establish. Only 30% of people established a crop of either clover. There was very little difference in establishment between the Persian and crimson clover, so the results reported are for both crops.

There are a number of reasons for failure in establishment. Many people assume slugs are the main culprit for any crop not establishing, and this can’t be ruled out. However, in the crops we grew at Ryton organic gardens, and in green manure crops grown on commercial farms, we often found evidence of extensive weevil damage. The Sitona weevil takes characteristic notch shaped bites out of the leaves. In a rapidly growing, healthy crop, this damage may set the crop back, but it is not enough to kill it. However, under conditions conducive to slow growth, such as cool weather or dry soil, the damage can be enough to prevent the crop establishing.

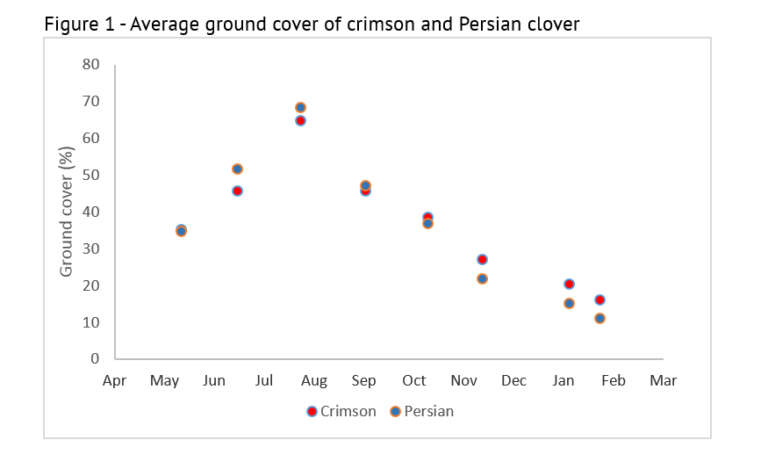

Those crops that did manage to establish, grew well. The average crop attained a ground cover of just under 70% by the end of July, then this declined from August onwards as the crop died down. The two crops flowered at similar times, towards the end of June (see Figure 1 below). Crimson clover produced bright red flowers, and Persian clover produced pink and white flowers.

After October, the crops had died back, and dead material was left on the plots. We asked members to leave the mulch to rot down over the winter until the following spring and assess its condition.

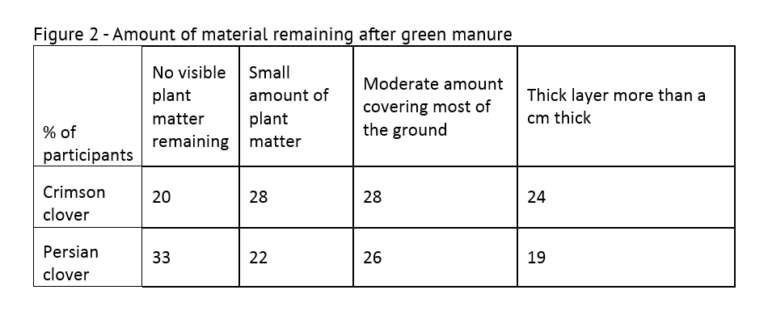

The amount of mulch remaining varied, with no material left from some crops whilst others left a thick layer of material (see Figure 2 below).

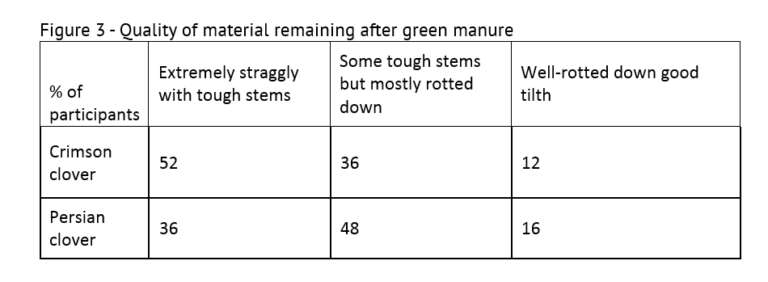

Members also assessed the quality of the mulch that was left. The Persian clover rotted down slightly better than the crimson clover, although there were still some tough stems remaining in the majority of both crop types (see Figure 3 below).

Conclusion

We asked members if they would grow Persian clover again. The response was mixed, and given the poor establishment of many crops wasn’t a surprise. We found that 32% definitely wouldn’t grow it again and 42% might consider it. 19% said they probably would grow it, and only 7% said they would definitely grow it again.

Most of the comments centred around the frustration of not being able to establish a crop and that it wasn’t very competitive against weeds in the early stages. However, the Persian clover was not significantly worse at establishing than the crimson clover. There were positive comments about the flowers and how they were attractive to bees.

Overall, growing Persian clover or crimson clover had a low rate of success amongst our members. This could partly be put down to the lower than average soil temperatures. Unseasonal weather conditions can cause problems when planning ahead for a nationwide experiment, as it does not allow for the flexibility of decision making that a gardener might make when operating independently. The Persian clover did die down to make a mulch that was easier to incorporate than the crimson clover, but there were still pieces of dried out material that were quite tough. From our experience, other green manures such as vetch are more vigorous and might be easier to establish than clovers, but they will tend to leave behind more tough plant material that is difficult to dig in.